The first drive that could qualify as overlanding in Africa was undertaken by a Briton called Robert L. Jefferson. Hard on the heels of the first horseless carriage, he set out in 1907 in nothing more sophisticated than a single-cylinder “dog-cart” Rover. The sort of Veteran you see struggling to get up Crawley Hill on the London to Brighton every November. Tall wheels, an 8 hp-engine the size of a lawn-mower and with so little space that the tools were in a small box under the floorboards.... the Rover was an unlikely vehicle to conquer Africa.

A single cylinder Rover 8hp

Jefferson was no hair-brained eccentric. He theorised that rather than burden a heavy car which then needs heavy axles, heavy wheels, and heavy chassis, he bucked all the conventional wisdom with a “travelling light is best” mentality. He wanted a car that he could push, alone, or, maybe just a few locals could help pull him through difficult terrain. Small engines need less petrol to carry.

In the early part of 1907 – the same year as Prince Borghese and his four rivals set out on the Peking to Paris – Jefferson and South African motoring pioneer Frank Connock drove the Rover from Durban to Cape Town, via Johannesburg. It cannot be claimed as the first crossing of the African continent, but the journey took 16 days and, at that time no other motorist had achieved such a long drive.

Jefferson had already proved his theory of travelling as light as possible by becoming the first ever driver to drive across Europe – again in his 8-hp single-cylinder Rover... Several drivers had tried it, but had been defeated by the goat-tracks in the mountains of Romania and Bulgaria. But in 1905, carrying only spare tyres and minimal luggage, he set out from The Autocar magazine’s office in Coventry, managed to get through the Balkans, and so became the first driver to reach Constantinople (Istanbul). He returned home to be hailed a hero.

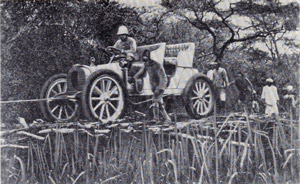

Back to the top...The first real crossing of Africa was completed in 1908, by a well-supported German team, who aroused so much interest “national pride” was at stake to the point that even the Kaiser was to support the attempt. Oberleutnant Paul Graetz, of the Imperial German Army, had served in German East Africa in 1902, on a road building programme. It gave him the idea to become the first to cross Africa by car, and on the same day that the intrepid Prince Borghese rode across the finishing line of the 1907 Peking to Paris, Graetz set out in a 40 hp six-litre Gaggenaue, a vehicle very similar to Borghese’s six-litre Itala. Fuel tanks for 625 miles were fitted, giant wooden wheels, 48 inches in diameter, were specially made, giving 14 inches of ground clearance. Like Borghese, he startled the locals wherever he went – they had never seen a car before. His aim was to cross Africa from Dar-es-Salam to Swakopmund, on the coast of German Namibia, reckoning it could be done in just six weeks.

Graetz crosses a handmade bridge in 1907-09

First troubles were encountered in the crossing of the Rufuma river, the car sank and became glued in the mud at the bottom. Once on the far side, Graetz decided to ditch vast quantities of provisions and spares, learning lessons the hard way the car was stripped to just an emergency seat on the chassis, and an absolute minimum of personal gear.

Then a chain of disasters struck. Crossing the Ugamberenga river, water got into the engine, and cracked all four of the separate cylinder blocks. They had now a useless car, after just one week on the road. The car was towed across the veldt to Kilossa, and a crew member despatched back to Germany to find new parts. The runner fell ill in Dar-es-Salam and decided against returning – it was three months before spare blocks were sent, and even then they were put on the wrong boat. A new chauffeur arrived, a man named Koch, who brought not just new engine bits but a whole new front axle – this was not needed so was left in Dar.

Delays had meant the crew were now facing the rainy season. Most bridges were only designed to carry men in single file, or, the odd ox-cart, and the crew needed gangs of natives to rebuild bridges and haul the car with hours of back-breaking labour. When a fall bent the front axle, a runner had to be sent back to fetch the spare, causing more delays. Rocks were blasted away with dynamite. Four months in from the start, the car had covered 625 miles.

Perhaps the horrors of Graetz's epic put others off. In 1914 this Belgian F.A.B. of Reinelt and Evanepoel set out from Cape Town for Cairo... with an 80-gallon fuel drum. They turned back after just 37 miles on hearing that a rival crew parked under a tree, disturbed a sleeping leopard, that promptly killed and ate the driver

Somewhere on the road to Lake Tanganyika, the car lurched into a sudden hole in torrential rains, and Graetz found that splitting the sump had caused the crankshaft to be twisted, all the bolts attaching the flywheel to the shaft sheared, and the clutch plate split. There was no hope of repairing it for 70 miles. A team of porters was assembled to pull the car – at one point 200 were needed.

Their entry into British Northern Rhodesia was marked by almost a month of gruelling toil, with miles of swamp. Another set-back was running out of fuel – it took a month for supplies to find the crew. In the heat, the monotony got to the crew, who played draughts with nuts and bolts, when they were found they were living on small game they had shot themselves and were drinking out of stinking, muddy puddles.

Crossing the Zambezi by using the railway bridge near Victoria Falls, the crew were put on the wrong road, and ran straight into a bush fire, the tyres were burned clean off the wheels before they managed to burst through a corridor of flames. Miraculously, the fuel tanks were unscathed. The crew limped on to Bulawayo, and then Palapye Road on the edge of the Kalahari Desert. It had now taken so long, the 1908 rains were about to set in so the crew altered course for Pretoria and Jo’Burg, to spend their second Christmas on the road in some comfort.

The final 2,000 miles saw drifting sand and stony desert, and petrol consumption in low first-gear falling to less than two miles per gallon. With fuel dumps hidden in the ground marked by stakes with metal tags attached, the going was slow. They ran out of water, and co-driver Gould, racked with thirst and in complete despair, finally resorted to drinking petrol. Attacked by fever as a result, for four days he lay between life and death. Oxon towed the car and crew to Chansi, where they found fuel and supplies, and welded up a broken valve. One day, they heard an almost forgotten sound – a dog barking. The crew had discovered a lonely Boer farm. Milk, butter, eggs were greeted as luxuries. The following day, a patrol of German cavalry from the fort at North Rietfontein came across the car – as soon as Graetz spotted his flag, he knew his problems were now over. They entered Swakopmund 18 months to the day after leaving the Indian Ocean. The 5,625 miles had been averaged at just nine miles a day.

It was an all-German triumph, but it was almost as if the horrors of African travel were to put off all other attempts – it was not until 1924 that a Cape to Cairo run was successfully achieved in something resembling a normal car.

Back to the top...

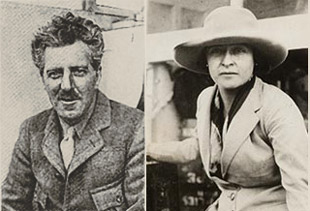

Major Chaplin & his wife Stella Court-Treatt

Major Chaplin Court Treatt, a former Royal Flying Corps pilot who had worked on airfield construction on 2,000 miles of the Trans-African air route between northern Rhodesia and Cape Town, knew what he would be up against. Major Treatt, however, made things more difficult for himself on insisting that the route was not to diverge from the “pink” bits of the map that were in British hands. He would be accompanied by his wife, Stella, and he chose two 30 hp Crossleys, which he had seen in action in the First World War. The body was turned into a pick-up truck, and the rear axle converted to twin-wheels, giving him a light six-wheeler. Wings were made of fabric. A four man crew, including a journalist by the name of Law from the Daily Express, were to join the Treatts. They were flagged away from Cape Town City Hall on September 28, 1924, by the Mayor and officials from the Automobile Club of South Africa. Hampered by mud, it took 25 days to reach Bulawayo. The journey from here one was now one of a battle against the elements.

The Crossley is loaded on a pontoon

Here they spent several weeks while a suspect axle was replaced, and a trailer was built to take some weight off. The 380 miles to Victoria Falls took four months, of thick slimy mud. Trees were cut down to put under wheels, parties of oxon hauled the cars and often progress fell to two miles a day. Torrential rains fell every day. Doors, lights, windows, and much kit was jettisoned along the way to lighten the loads. The weather was against them – from Wankie to Livingstone, normally a day’s run, would see the team bogged down completing the 50 miles in a month. They eventually reached the luxury of the Falls Hotel, and a local station master, complete with cap, whistle and green flag, escorted the car across over the Zambezi on the rails.

Their troubles were only just beginning for now bridges had to be patched up or built, often as often as every 500 yards. September 30, a year and six days after leaving Cape Town, the Treats finally entered Nairobi. Here things improved, taking a route into Uganda, they crossed the Sudan border eight days after leaving Nairobi. They crossed the Nile on October 23, on a barge only just big enough to take the two cars. Rains began to pour down steadily, as the crew hacked their way through marshy ground. They finally saw their first Arabas at Abu Matarik, on December 14. Their second Christmas on the road was celebrated with turkey eaten off fuel cases at El Obeid, while waiting for new wheels to arrive from Khartoum. At Wadki Halfa, they received a telegram from Cairo. It read: “Halfa to Shellal quite impossible by car.”

In the enormous expanse of desert between the Nile and the Red Sea, the two Crossleys became lost, but eventually stumbled over the Aswan Dam and drove into Luxor. Four days later, with clothes that were rotting on their backs, the Treats drove into Cairo, to be met by the Egyptian Automobile Club, and Government representatives.

Back to the top...

The Citroen Africa Expedition of 1924

The first complete motorised crossing of the whole length of Africa was a distinction claimed by the Citroen Central Africa Expedition of 1924, who became the first to cross the Sahara from north to south, having married tank technology with a truck to produce a tank-like tracked vehicle that could cope easily with sand or mud. Renault joined in and also produced a cross-country special, and in 1925 drove from Colomb-Bechar and through the Tanezdrouft to Niamey, then across the centre of Africa to Lake Chad and Stanleyville to Nairobi, then south Livingstone and on to Pretoria, Jo’Burg, and Cape Town. This just snatched the glory from the Treatts and their Crossley, but at least the Treat’s could claim to have driven the length of Africa in something resembling a normal car. They were also the first to drive the whole of Africa in two-wheel drive.

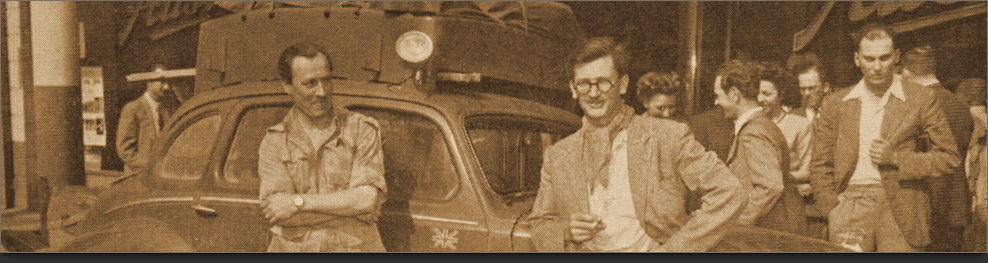

Alan Gilg and Walter Kay with their Morris 8

The first small-car to crack London to Cape Town is generally accepted as a feat chalked up by Alan Gilg, who, when jilted by a girl he had fallen head over heels for with the excuse that he simply wasn’t manly enough for her liking, set out to Cape Town to prove to himself he really was as bold and dashing as anyone else... he met Walter Kay, a pilot recovering from a near-fatal crash having flown into a radio mast, at a New Year’s Eve party in the Piccadilly hotel. The year was 1933.

They set out for Folkestone a few days later in Alan’s Morris Eight convertible – the only modification having been carried out at the Cowley factory to lower the already low back axle ratio.

They drove to Morocco – had to turn left to avoid the Atlas Mountains because the Rifs had risen, made it along the coast to Algiers, and then turned right to go south to Reggan, Niamey, Kano, and across the centre of the Dark Continent to Stanleyville, Nairobi, and on to Broken Hill, Victoria Falls, Bulawayo, up to Salisbury, and then Jo’Burg, finally making it to Cape Town.

Total fuel consumption was 537 gallons, and 15 gallons of oil – considered normal at the time!

A Yorkshire TV researcher found some good quality film which Gilg had shot, and turned it into a documentary, and wrote a book from diaries – Turn Left The Riffs Have Risen, Edited by Barry Cockcroft, is an engaging book on a pair who reasoned “we only did this because we were looking for something to do.”

Back to the top...

Hinchcliffe & Bulman - 1951 Hillman Minx

The first attempt at driving non-stop across Africa from London to Cape Town was made by motoring journalist Humphrey Symons and his friend, Bertie Browning, who borrowed a press-demonstrator Wolseley 18/85, and completed the run in 31 days despite crashing through the railings of a bridge in the Congo, and having to swim out of a crocodile infested river with a broken shoulder.... the following day, over 50 prisoners were despatched from jail to help haul out the waterlogged car, which was patched up, and drove on to claim the first World Record.... it was January, 1939.

In December 1949, the record was taken in fine style by Ralph Sleigh and Peter Jopling in the new Austin A70, chopping the record down to 24 days, 2 hours, 50 minutes. Ralph went on to chalk up non-stop records for crossing the Sahara, via Tamanrasset in southern Algeria to Kano in Northern Nigeria. Publicity gained for Austins particularly in important export markets were column inches the rivals at Rootes of Coventry felt they just had to do something about, so Hillman, and then Humber, joined the fray.

In 1951, George Hinchcliffe and James Bulman prepared their own Hillman Minx and drove from Bradford to Cape Town in 22 days.

Hinchcliffe, Walshaw & Longman set a 13 day 9 hrs London - Cape Town record in this Humber

This was the year of “Cape Fever” as Henri Berney and Henri Loos, drove an American Ford V8 Convertible from the Cape to Algiers in 16 days, which clipped three days off the time set by Mercier and De Cortanze in a long-wheelbase Peugeot 203.

Having driven it in his Minx, George Hinhcliffe proved to be a glutton for punishment as he returned in a works-supported Humber Super Snipe, and by using two co-drivers, so the car could be driven virtually continuously, and an air-lift from Marseille, they got the time down to a remarkable 13.5 days to Cape Town’s Town Square, from London’s Trafalgar Square. This was the record Eric Jackson only just managed to beat eleven years later in a Ford Cortina – he lost time avoiding floods and beat Hinchcliffe by mere minutes.

Then in 1951, the Algiers Motor Club set about turning it into a rally – joint winners were a Delahaye, a Jeep, and a Land Rover. The event was made more competitive for the second running in 1953, won by a Fiat 1900, with a 1100cc Moretti second.

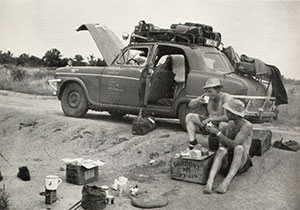

The amazing Richard Pape in Cameroon mud with his trusty Austin A90, driving from the Cape at the top of Norway to Cape Town — claiming a new first and beating rival Renault Dauphine

What do you do if you survive World War II after jumping out of a Stirling Bomber, plotting daring escapes with Douglas Bader, putting up with several interrogations by the Gestapo, and succeed in getting back to Blighty, only to then discover after its all over that you just can’t settle down to life’s ordinary rut, like all the rest?

Richard Pape thought the “export or die” attitude of the British motor-industry was all very well, but, what they should be doing in the post-war 1950s is to prove themselves to the rest of the world that British engineering really was the best. So, he came up with the scheme to drive the latest model from the British Motor Corporation, a six-cylinder 2.6 litre Austin A90 four-door saloon, from the cape at the northern tip of Norway, to Cape Town. Nobody else had driven from cape to cape, and this “first” had Richard Pape really fired up.

Bombastic, arrogant, argumentative, single-minded, incredibly determined, Richard Pape had many of the right qualities – the sort that had got him out of Nazi concentration camps and home. Nobody could tell him anything, least of all the word No. He fell out with his navigator on the run up through Norway – hardly a surprise – who was so angry he stepped into the nearest car showroom, a Renault dealership, bought a Renault Dauphine, and announced that he would race Pape to Cape Town.

When Pape's second co-driver became seriously ill at Gibraltar Pape knew that crossing the Sahara alone and at the height of summer was against the regulations and that he would not get a permit from the French. He needed another co-driver, so he walked into the RAF Sergeants mess, regaled them with his wartime escape stories.... after all, having written two best sellers, Arm Me Audacity, and Boldness Be My Friend, Pape was something of a celebrity. He persuaded – remarkably – a young RAF flight sergeant to go AWOL and accompany him. “But I will get court-marshalled if we are caught.” Ah, says Pape, if the Nazis can't catch me... They made the Sahara crossing, but not without provoking a massive search that would end in their arrest and further delays.

Richard Pape and Johan Brun take lunch beside the road in Equatorial Africa.... a Gordon's Gin box serves for a table

In Nigeria, the rains were heavy and the roads flooded. At one of many road-blocks, Pape was told it was impossible to continue. “Ah, but I must,” he insisted... and produced a visiting card, which he had the foresight to print in England before setting out, and now the visionary initiative was to produce dividends. It showed that Richard Pape was a Nigerian Health Inspector, and he had a hospital to inspect.. “its only just down this road.” Policemen were not going to stop the flying Pape. Bullshit, persistence, dogged determination, all saw him through... and so the car arrived in Cape Town.

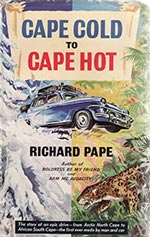

Pape's book cover

The youth of the 1950s might have been inspired by Boy’s Own and Biggles, but now they had a new real-life hero in Richard Pape, who achieved a stunning race across the length of Africa in a car bought out of a showroom just days before setting out. The car today stands in silent testimony to a brilliant achievement in the Heritage Motor Museum in Gaydon, just off the M40 near Warwick. It still has the broken front spring that creaked as it limped into Cape Town on, and so sits a bit lopsided, and in the boot, are all the spares Pape had packed, along with a box of original 1950s Bronco toilet-rolls, baked brittle and as hard as tracing-paper by the Sahara sun.

Pape's book about this drive, Cape Cold to Cape Hot, was written in the heavily timbered, black and white cottage of The Priest’s House, Stratford St. Mary, near Colchester, in Essex, tapped out on a portable typewriter on a table to the left of a large open fireplace, and was published in 1955. Someone should put a blue plaque on an outside wall of this medieval house as a memorial to Richard Pape, author of three remarkable books.

Philip Young recalls

After reading Cape Cold to Cape Hot in 1995, I heard Pape was living in Australia, but nobody knew where, and fascinated by all his adventures, thought it worthwhile to try to track him down. International Directory Enquiries in those days would allow three numbers for one call, so, each night, I put in a couple of calls, got six numbers, and dialled them, armed with a Times Atlas of the World, picking out town names from the map of Australia, starting on the west coast at Perth. Each night, I would work my way across the map, dialling six numbers, asking if they were Richard Pape who, er, sorry to bother you, but who once raced an Austin A90 across Africa.

It was fortunate that there are not many R. Pape’s living in Australia, and I soon found myself on the East Coast, having gone through Melbourne, Adelaide, Darwin, Sydney... and was about to give up, when the very last call got a croaky elderly woman answering... “maybe, and maybe not... who wants him?” Once again I gave the ludicrous-sounding reasoning for the call. “Well, he is in the front room, you know he is not very well... in fact, he is very seriously not well.” I had finally found the author and driver of the Austin Africa Mk 1. There was then a lot of shouting... Richard’s wife knew how to answer back in no uncertain terms to a cantankerous old bore, who these days didn’t want to talk to anyone. I told Richard about the car, and how I had driven it out of the museum after fitting a new battery to take photographs for Classic and Sportscar Magazine. “Does it still have a bloody broken front spring?” Indeed, it does. “Makes no bloody difference – it always steered like a ruddy wheelbarrow.”

Did he still have any his cine film? “No, it was in the attic - it was all burnt when I set the house on fire...

....I’m glad the car is still as I handed it to Austins... but... now you’ll have to bugger off.” The phone call ended as abruptly as it started. They were possibly the last words Richard gave to anyone other than his wife and his doctor. Richard Pape died of stomach cancer a few days later.

In 1950 came the first of a series of French-run Méditerranée - Le Cap events, a 10,000 mile (16,000 km) rally from the Mediterranean to South Africa. The event ran on and off until 1961, when the new political situation made further events impossible.

Here we have a film clip from the 4th edition of the event in 1959. The rally started from Algiers on January 8th and from an initial field of 28 participants it is thought that 16 teams reached Cape Town from February 20th.

Former Grand Prix driver Karl Kling and Rainer Günzler won the event in their Mercedes 190D with Olivier Gendebien and Lucien Bianchi second in a Citroën DS19. British honour was upheld by Gyde Horrocks and Peter Riviere in a Land Rover.

Eric Jackson and Ken Chambers - Ford Cortina - claimed the fastest ever drive between London and Cape Town

Eric Jackson was a rally driving Ford Dealer from Barnsley who became a legend of long distance drives during the sixties. In addition to two record drives between London and Cape Town he also completed a 42 day round the world record in 1967 and took part in the first London to Sydney Marathon in 1968 during which he sacrificed a good position when his cylinder head was given to Roger Clark.

In early 1963, soon after the new Cortina was launched by Ford, Eric accompanied by Ken Chambers set a new London to Cape Town record. Taking a route by way of ferry from Marseilles to Tunis, they went via Cairo and Nairobi, reaching Cape Town in 13 days 8 hours and 48 minutes, which was claimed to be just 18 minutes faster than the previous record.

Ken had a heart stopping moment on arrival into Cape Town – it was late at night and he couldn’t find the Nelson Hotel, knowing that the time-keeper from the South African Motor-Sports Club was in the bar. He drove round and round, could see the hotel, “but couldn’t for the life of me find the entrance,” says Eric.

“Panic set in, so I drove over the pavement, through some rose bushes, in an attempt to park it on the lawn, but the back wheels dug in, and all I did was sit still, wheels spinning, chucking dirt out all over the grass.” The time-keeper, who had been at the bar rather a long time, was found by a Bell Captain, who helped him out to the lawns where he stopped the watch.

In 1965 Eric Jackson raced the Windsor Castle ocean liner from Cape Town to Southhampton

Ford were pleased with Eric’s effort in the Cortina, so a couple of years later in 1965 they planned a publicity stunt to race the liner RMS Windsor Castle from Cape Town to Southampton. This ship, the last passenger liner built at Cammell Laird in Birkenhead and last of the Union-Castle mailships that sailed between Southampton and South Africa, would average 24 mph and Captain Hart thought it a no brainer – he would win. Jackson set off in the Corsair but lost time with a string of punctures. He used Firestone cross-plies, and found the inner tubes were rubbing badly by the ribbing inside the tyres. Cross-plies, he argued, are available all along the route and have stronger side-walls – but it proved to be a duff choice, and the car’s progress suffered. At one point, Eric was changing tubes, fixing a puncture, on the move!

Cameroon refused the car so it had to be flown in an air-lift – and at a stroke was no longer keeping the wheels on the ground. They then drove non-stop to England, reaching a hotel at Gatwick the night before the day the ship was due to dock, the crew took a hotel room for a few hours rest and then drove to Southampton. Ford publicity chief Walter Hayes had agreed with Captain Hart that due to the air-lift, they would call it a draw, and the Corsair made it to the dockside as the ship entered the harbour.

In 1983 John and Lucy Hemsley - Range Rover - set the record for the all overland drive from Cape Town to London taking 14days, 19hrs, 26mins

The current record-holder for the all overland dash between Cape Town and London is held by Brigadier John Hemsley, who as an Army Major lead the British Army Team in various international rallies. Having started in racing John took up rallying in 1963. During the next twenty years John competed in over fifty international events around the world driving works cars for Ford, Peugeot, Rover, Leyland, Rootes, Mazda and Subaru.

Early in 2010 we had the pleasure of meeting John, now 75, who today lives in very active retirement on a farm outside Bath. His Cape Town - London record is slightly different from that set by Eric Jackson in the Ford Cortina, in that it didn’t claim any neutral-sections for crossing the Mediterranean. Instead their route skirted east of the Mediterranean through Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Syria and Turkey to make it a true overland drive with the English Channel as the only sea crossing.

Driving without service support in a works-supplied Ranger Rover, prepared by Tom Walkinshaw, sponsored by fizzy-drinks company Soda-Stream and co-driven by Lucy, his wife of a few months, they set the record at 14 days, 19 hours, 26 minutes. Their departure time was authenticated by the South African Automobile Association with the finish clock in London manned by Neil Eason-Gibson of the Royal Automobile Club's Motor Sports Association. Neil sat in a deck chair under Marble Arch from 5:00am having received a phone call made by motoring journalist Michael Scarlett of Autocar from Dover saying that the Range Rover was on the A2.

The Range Rover had averaged over 80 mph including refuelling from Yugoslavia across Europe, so keen were they to get home. In fact Neil stopped the clock on their arrival at 5:26am, then sent them off to have a wash and get changed and return when it was daylight so photographs could be taken, so the finish was spoofed up for motoring magazines and the press.

John and Lucy Hemsley traversed vast trackless deserts, crossed 17 borders and escaped bandits and bureaucrats on their epic 12,000 mile journey

Mistaken as a terrorist raiding party they were shot at in Sudan, with machine guns peppering the Nile but missing the crew and the vehicle apart from one bullet hitting the front bumper, and they were detained in a cell in Syria. This was their biggest delay and could have shaved some hours off the record had this mishap not befallen them.

Holed up in a small cell, with no toilet facilities and only a single bed between them, Lucy Hemsley noticed a wire hanging from a wall that ran out to a telegraph pole - it was the remains of a telephone. Through a window she persuaded some children to swop her bar of chocolate for a telephone, and the kids came back with a "candlestick" vintage telephone. Undoing the plate at the bottom with a nail file, they found five terminals. The wire had seven threads. The combination of what of the seven wires should go on which of the five terminals was a brain-teaser that occupied the prisoners for over two hours of trial and error. It took 2.5 hours to work out how to connect the phone to the wire, and with a notebook of telephone numbers, John was able to call up the British Ambassador. He was at a dinner part and said he couldn’t help till the morning, but would get them out.

In the morning, the crew were released with fulsome apology. "In high dugeon and bloody angry, we tried to roar away, alas, the Range Rover had clogged up air filters and the bloody engine wouldn't fire up," recalls John.

He was given a certificate by the RAC to record his feat, a letter of confirmation from Land Rover's marketing department (apologising for the lack of effort by the publicity department), and a letter from John Davenport, Manager of the Leyland Competitions Department, congratulating the pair on a remarkable effort.

The Range Rover arrived in London on February 16th, 1983, and went into the Guinness Book of Records, and remains unbeaten to this day. John's success, he reckons, was chiefly down to not stopping, for nobody... "after Tanzania, the entry into Kenya was delayed as the right person who does the stamping was at home.... we just drove off without a passport stamp, argued our way at exit of Kenya, and in fact didn’t have any passport stamps when we entered Syria... that was the chief reason for our detention."

John drove in over 50 international rallies but setting the record for the fastest continuous drive between Cape Town and London has to be his crowning achievement.

In October 2010 the Max Aventure team of Mac MacKenney, Chris Rawlings & Steve MacKenney drove a 10 year old Land Rover Discovery 2 Td5 from London to Cape Town covering 10,000 miles through 20 countries in 11 days 14 hours and 11 minutes breaking the previous London to Cape Town record of 13 days, 8 hrs 48 mins set in 1963 by Eric Jackson & Ken Chambers.

Back to the top...